Sigu, Véronique. Médiévisme et

lumières: le Moyen Age dans la ‘Bibliothèque universelle des romans'. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, August 2013 (SVEC 2013:8).

Sigu, Véronique. Médiévisme et

lumières: le Moyen Age dans la ‘Bibliothèque universelle des romans'. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, August 2013 (SVEC 2013:8).

Reviewed by

Jessica Stacey, King’s College London (Jessica.stacey@kcl.ac.uk)

That the Middle

Ages were not highly regarded by eighteenth-century French society is widely

known. This is the age of Voltaire writing of the dismal, barbaric birth of Europe,

of gothique as a byword for confusion

and ugliness, reaching its apogee in the neo-Classicist French Revolution.

However, it is also in the eighteenth century that French medievalist

scholarship is born with the work of antiquarian La Curne de Sainte-Palaye, who

wrote memoirs on chivalry and troubadour poetry which made their way to Horace

Walpole’s library at Strawberry Hill.[1]

Alongside this serious scholarship, medievalist (or medievalish) short stories were rapidly gaining

in popularity. Paperback collections, or bibliothèques, such as the populist Bibliothèque bleue made folk tales and

characters dating back to medieval romance cheaply available to an expanding

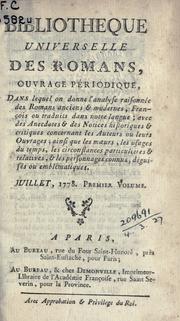

reading public. It is amidst these contrasting strains of thought that, in

1775, the first volume of a new project, the Bibliothèque universelle des romans, is published. The title page is graced by an ambitious

mission statement to which Véronique Sigu frequently returns over the course of

her new study, Médiévisme et Lumières: le

Moyen Age dans la ‘Bibliothèque universelle des romans’, and it is worth quoting

this key passage at the outset: ‘La Bibliothèque

universelle des romans, ouvrage périodique dans lequel on donne l’analyse

raisonnée des romans anciens et modernes, français ou traduits dans notre

langue; avec des anecdotes et des notices historiques et critiques concernant

les auteurs ou leurs ouvrages; ainsi que les mœurs, les usages du

temps, les circonstances particulières et relatives, et les personnages connus,

déguisés ou emblématiques.’[2]

The BUR is interested in the process of

categorisation. This process was key to the formation of what Roger Chartier,

in a well-known article which Sigu cites more than once, dubbed ‘libraries

without walls’: encyclopaedic or exemplary collections of texts, in vogue since

the seventeenth century.[3]

As a universal library of novels, the

BUR posits eight distinct classes

according to which all novels can be ordered, and the second of the eight

categories is romans de chevalerie.[4]

It is on these extraits (extracts)

or miniatures and their analyse raisonnée that Sigu focusses, also

drawing occasionally on the third category of ‘historical’ novels, to elucidate

her thesis on the role of the BUR in

crafting a place for the medieval in both popular and intellectual thought.

The Bibliothèque universelle des romans has

garnered criticism for its pretensions, which were lofty: the editors, working

from the Marquis de Paulmy’s extensive collection of manuscripts and with the

help of the antiquarian La Curne de Sainte-Palaye, aimed at a more

sophisticated audience than the Bibliothèque bleue but, as Lise Andries has shown, BUR

extracts were often based not on manuscripts but on the Bibliothèque bleue itself.[5]

Sigu acknowledges this charge, but seeks to elevate the collection’s status for

both medievalists and eighteenth-century specialists by emphasising both the

project’s commitment to ‘serious’, manuscript-based medievalism (especially in

its earlier years), as well as the close ties between those working on the

project within philosophe

as well as antiquarian circles. Sigu makes the philosophical stakes of her project clear in the

introduction: as the philosophes often

mocked erudition and erudite scholars were frequently hostile to the philosophes, the possibility of the BUR as a site of crossover renders the

periodical interesting to those who focus on the history of ideas as well as to

those who focus on the history of medieval reception. If accepted readings of

intellectual currents in the eighteenth century see reason (philosophy) opposed

to memory (erudition) in epistemology, and reason triumphant with far-reaching

implications, Sigu seeks to establish the BUR

as a location in which these opposed forces might, to some extent, be

reconciled (15). Hence the work’s title, which unites rather than opposes médiévisme and lumières – medievalism and Enlightenment.

To elucidate this

claim, Sigu begins her analysis with portraits of the two major personalities

behind the BUR, the Marquis de Paulmy

(who guided the publication from 1775 to 1778) and the Comte de Tressan (who took

the reins after Paulmy’s somewhat acrimonious and mysterious departure). Sigu

situates the two men in French intellectual life with reference to the salons

they attended. We learn that both would have mixed extensively with Montesquieu

and Voltaire at the salon of Madame

Tencin, as well as attending the salon of Madame Doublet where the antiquarian

La Curne de Sainte-Palaye made his intellectual base. She reveals the

surprising fact that the two men were closely linked with the philosophe par excellence, Voltaire, who was invited

to the editorial board and seemed, at the age of eighty, regretful of having to

decline (17). Whilst acknowledging that there is a schism between the time of

Paulmy and the time of Tressan – the loss of the former’s extensive library as

a resource seems to have led to a more slapdash, less antiquarian approach –

she argues that the Bibliothèque

universelle des romans took two major ideological stances towards the

Middle Ages, created under Paulmy’s reign and continued, even reinforced, under

Tressan’s. These stances are, firstly, a particular ideology of fiction and

history which seeks to rehabilitate the novel or romance through its historical

content, and secondly, the creation of the medieval as a site from which ideal

masculine models, both aristocratic and patriotic, can be drawn.

In arguing for a

rehabilitation of romans through

their historical content, Sigu is engaging with an anxiety foundational to

eighteenth-century medievalism. Novels and romances become valuable for their faithful portrayal of the customs and

morals of past times; the BUR was

following La Curne de Sainte-Palaye who, in his Mémoires sur l’ancienne chevalerie (developed during the 1750s) had

set out an extensive defence of using fictional texts to ground assertions

about history and about actual medieval life. These same novels or romances

were, however, considered potentially dangerous, and this is the crux of the BUR’s engagement with fiction – what are

its safe uses and what, when making an extrait

or miniature should be excluded,

or even rewritten?

In a fascinating

discussion of the implications of the term extrait,

Sigu convincingly argues that we must take its origins in chemistry seriously.

The BUR generally masked the more

violent or sexual aspects of medieval texts, figured as dangerous,

inflammatory, or simply poor-taste: medieval writing must be ‘distilled’ to

recover only the useful or harmlessly diverting. Infamous anti-philosophe

Fréron, reviewing the BUR in 1775,

praised the process in intriguingly chemical language: ‘D’après ce que j’en ai

vu, j’ose dire que tous ces ouvrages lus dans la Bibliothèque en question, non

seulement n’ont plus rien de dangereux, mais qu’ils contiennent les plus grandes

leçons de sagesse et d’excellents préservatifs contre les séductions du vice.

Le poison secret qui pourrait s’y

trouver renfermé reste dans le creuset de

l’analyse, laquelle se borne à donner l’esprit

et, pour me servir de l’expression même des auteurs, la miniature de chaque

roman: miniature dans laquelle n’entrent que les traits propres à caractériser

l’ouvrage, et d’où sont bannis toutes les images qui ne seraient pas avouées

par la décence la plus rigoureuse.’ (quoted

120-121, my emphasis)[6]

As Sigu notes, what is conserved is the fond

historique (historical foundation), and what is left out is the imagination en délire (fevered

imagination) of pre-modern writers.

In a fascinating

discussion of the implications of the term extrait,

Sigu convincingly argues that we must take its origins in chemistry seriously.

The BUR generally masked the more

violent or sexual aspects of medieval texts, figured as dangerous,

inflammatory, or simply poor-taste: medieval writing must be ‘distilled’ to

recover only the useful or harmlessly diverting. Infamous anti-philosophe

Fréron, reviewing the BUR in 1775,

praised the process in intriguingly chemical language: ‘D’après ce que j’en ai

vu, j’ose dire que tous ces ouvrages lus dans la Bibliothèque en question, non

seulement n’ont plus rien de dangereux, mais qu’ils contiennent les plus grandes

leçons de sagesse et d’excellents préservatifs contre les séductions du vice.

Le poison secret qui pourrait s’y

trouver renfermé reste dans le creuset de

l’analyse, laquelle se borne à donner l’esprit

et, pour me servir de l’expression même des auteurs, la miniature de chaque

roman: miniature dans laquelle n’entrent que les traits propres à caractériser

l’ouvrage, et d’où sont bannis toutes les images qui ne seraient pas avouées

par la décence la plus rigoureuse.’ (quoted

120-121, my emphasis)[6]

As Sigu notes, what is conserved is the fond

historique (historical foundation), and what is left out is the imagination en délire (fevered

imagination) of pre-modern writers.

The primary issue

that can be taken with Sigu’s analysis of this process concerns how far it can

be considered a rehabilitation of the novel/romance form. She qualifies that

this rehabilitation is not wholehearted, comporting a moralising taint that the

reader may find paradoxal, but the

purification implied by this process of extraction – which results in something

which no longer has the form of a novel or romance – may be more significant

than Sigu allows. On the one hand, Tressan is happy to speak of the roman de chevalerie as valuable for having

‘point de modèle dans l’antiquité. Elle est dûe au

génie des François ; & tout ce qui a paru, de ce genre, chez les

autres Peuples de l’Europe, a été postérieur aux premiers Romans que la France

a produits, & n’en a été, pour ainsi dire, qu’une imitation.’[7]

On the other, content is pruned, and the form itself undergoes extensive modification to produce an easily

digestible miniature.

Sigu’s second

major argument revolves around the changing ideological function of the Middle

Ages in France towards the end of the eighteenth century. She identifies two

primary deployments of a medieval ideal in the Bibliothèque universelle des romans, roughly splitting between

Paulmy’s and Tressan’s directorships but present throughout the publication’s

history. The first is the chevalier as

critique of and model for the modern aristocrat, and the second is medieval

France as the birthplace of the modern French nation. Concurrent to the textual

and narrative harmonisation practised by the editors, there thus runs a

harmonisation of power dynamics between rulers and their vassals, which tends

to recast kings as absolute monarchs and knights as absolutely loyal – not

through a sense of feudal obligation, but through an anachronistic nationalism

(228). She quotes Tressan who, blending aristocracy and national progression,

figured chevalerie as a civilising

aristocratic force pushing society forward (139). Of course, not all knightly

characteristics fit this assessment. In a century which had forbidden duelling,

the central role of single combat was downplayed (147), whilst the religious

attitudes of the knights, uncomfortably close to superstition and fanaticism for

eighteenth-century thinkers, were also modified or skipped over, even when the

Grail Quest is at issue.

Rehabilitators of

the medieval past are interested in grounding French national character, and

particularly their gallantry in love, in the Middle Ages, but most (aside from

the notable exceptions of Boulainvilliers and his followers) seek to divert

attention from medieval political organisation. In common with other

eighteenth-century retellings of medieval tales (Baculard d’Arnaud’s Nouvelles historiques, for example), the

BUR expands (or even fabricates) a

principal role for individual sentiment, and elides the troubling

non-individuation of the medieval hero/heroine (‘son étrangéité’, 177) and the

primarily social function of courtly love. Furthermore, love of the

eighteenth-century kind is used to mask medieval political concerns:

Blanchefleur’s feudal war in Chrétien de Troye’s Conte du Graal is rewritten with the damsel besieged by a spurned

suitor (169). Sigu also demonstrates that greater emphasis was placed,

throughout the BUR’s treatment of the

medieval past, on conjugal rather than extramarital love, and convincingly

argues for a sexist undercurrent restricting female agency (notably, 176 on Guinevere

and Lancelot in Le Chevalier de la

charrette).

A minor criticism,

but one pertinent to medievalists, is that Sigu’s medieval secondary references

are rather venerable, whereas her eighteenth-century secondary sources are much

more up-to-date. This may, of course, be because she deals with

well-established medieval texts, whilst the study of eighteenth-century

medievalism is in the process of blossoming. This imbalance has no particular

negative impact on the investigation, but it might have been interesting to

reference more recent work by, for example, Carolyn Dinshaw on nineteenth-century

amateur medievalism. However, this is not to say that her work does not engage

with problems of contemporary relevance to medievalists for, by situating the BUR’s extract of The Perilous Cemetery in relation to the periodical’s editorial

technique more generally, she draws conclusions important to the manuscript

tradition of the medieval text. In contrast to the text’s editor Nancy Black,

who judges from the great disparities between the BUR version and the extant manuscripts that a lost manuscript must

have been known in the eighteenth century, Sigu demonstrates that the

variations from extant manuscripts to the BUR

version are no greater than those extracts for which the source manuscript

is known for certain, refuting the lost-manuscript theory (discussed 147-151).

Another moment which will bring a smile to the faces of medievalists is when

she cautions her readers with one of the fundamental elements of engagement

with medieval literary tradition, but applied to the BUR: ‘évitons [...] de juger trop sévèrement le manque de fidélité

de la reécriture à l’original mediéval, nous imposerions des critères tout à fait

anachroniques à ces travaux d’adaptation’[8]

(254). A medievalist Enlightenment indeed.

Sigu has

undertaken a formidable amount of research, supporting her analysis of the

ideological agenda of the BUR by

citing reviews from many contemporary journaux

which back up her assertions, suggesting a widespread engagement with, and

appetite for, the brand of medievalism the BUR

was selling. Her critical engagement with the implications of the metaphor

of chemical extraction is, overall, highly compelling. Her extended analysis of

the technique consistent throughout the BUR’s

publication (no matter who held the

reins) of distilling ‘unwieldy’ or ‘barbaric’ medieval texts down to a

particular conception of their essence, and then adding a great deal of moral

or historical commentary to produce a more coherent image of chivalry, builds a

convincing picture of a publication seeking to enhance the chevalier for eighteenth-century

reappropriation – though this by, ultimately, denigrating medieval literary

production. In identifying a move, as the publication evolves, from the

medieval figured as a place from which to criticise modernity to the medieval

as modernity’s origin point (244), Sigu situates the Bibliothèque universelle des romans at the heart of the current

revaluation of what medievalism meant to the Enlightenment.

Jessica Stacey

King’s College

London

[1] Mémoires sur l’ancienne chevalerie; Considerée comme un établissement

politique et militaire. 3 vols. (Paris: Chez Duchesne, 1759).

Histoire littéraire des troubadours, (Paris: Chez Durand, 1774) (Horace Walpole’s annotated copy held at the British Library, class-mark 1464 d.1).

Histoire littéraire des troubadours, (Paris: Chez Durand, 1774) (Horace Walpole’s annotated copy held at the British Library, class-mark 1464 d.1).

[2] The Bibliothèque universelle

des romans: periodical giving a reasoned analysis of novels ancient and

modern, French or in translation, including anecdotes and historical and

critical annotations regarding authors and texts, as well as the morals and

customs of the past, particular and related circumstances, and known, disguised

or symbolic characters.

[3] Chartier, Roger, ‘Libraries Without Walls’ in Representations, No. 42, Special Issue: Future Libraries (Spring,

1993), 38-52.

[4] As Sigu notes on 197, the term ‘roman’ (novel) as used by the BUR includes many forms not covered by

modern usages – medieval romances, contes,

even poetic retellings of history.

[5] Andries, Lise, ‘La Bibliothèque bleue

et la redécouverte des romans de chevalerie au dix-huitième siècle’, in Medievalism and manière gothique in

Enlightenment France, Damian-Grint, Peter (ed.), (Oxford: SVEC, 2006) 52-67.

[6] ‘From what I have so far seen, I dare say that all the works in

this Bibliothèque not only no longer

contain dangerous material, but that highly edifying lessons and effective

defences against the seductions of vice are to be found therein. The secret

poison which could have been hidden within is left behind in the crucible of

the analysis, which restricts itself to portraying the spirit or, to use the

favourite term of the authors, the miniature of each novel: miniature into

which are admitted only those traits necessary to convey the character of the

work, and from which are banished any images which the most rigorous modesty

would scruple to avow.’

[7] ‘no model whatsoever in Antiquity. It was a French invention, and

all other works of this genre which appeared in Europe were posterior to those

first novels/romances produced by the French, and were thus imitations of

them.’ Tressan, le Comte de,

‘Discours préliminaire’, in Corps

d’extraits de romans de chevalerie, (Paris: Pissot, 1782)

[8] ‘let us avoid judging the lack of fidelity to the medieval original

in the retelling too harshly, for this would be to impose utterly anachronistic

criteria upon these adaptations.’