Reviewed by: Thomas Lawrence Long (thomas.l.long@uconn.edu)

Editor Sarah A. Kelen has assembled eight thoughtful and well researched chapters, which she introduces in a chapter (“The Body and the Book”) that does more than summarize the scope and theme of the book, highlighting the collection’s preoccupation with images of both books and bodies. She begins with an allusion to the emerging field of adaptation theory but making an analogy between Hollywood’s appropriation of other media, on the one hand, and Chaucer’s borrowing of Petrarch, on the other. Analogously, how did early-modern Protestant authors appropriate medieval Catholic writers? The paradox as Kelen sees it is that “the ghost of the Middle Ages continued to haunt the early modern period because neither the tomb nor the text could wholly contain its occupants” (p. 1), which becomes particularly problematic when “the intertextual connections between early modern and medieval texts extend beyond literary fictions to historical, theological, and political writings” (p. 3). Here Kelen focuses her attention to the Tudor writing of history, where there was a keen awareness that the same medieval text might be used polemically to support opposing views. This emphasis agrees with F. J. Levy’s early insight and Jennifer Summit’s recent reformulation of the profoundly historicist character of the Tudor Reformation. Like the ruins of an abbey plundered for its worked stone to build a new Tudor edifice, early modern authors borrowed, sometimes quirkily, from medieval texts.

Body and book are much in evidence in Dan Breen’s chapter “The Resurrected Corpus: History and Reform in Bale’s Kyng Johan.” Breen observes that Bale’s play is not only the earliest extant play to represent kings but also one of the earliest to depict historians. The paradox of Bale’s play is formulated in the question: “what motive might a historian have to challenge a political dispensation that authorizes his work?” (p. 19). For Bale, the movement from manuscript to print culture enabled the publication of the documents of the English past (particularly after the dissolution of the monasteries) whose reading enabled members of the gentry (who could afford books) to “read English history . . . [in order] to learn one’s social role, and so by acting upon the principles gleaned from history study to make the shape of English society more coherent” (p. 22). Bale links “the act of memorialization” with “historiographical production” (p. 27) whose product is a reformed Church of England and a unified nation.

Kathy Cawsey’s “When Polemic Trumps Poetry: Buried Medieval Poem(s) in the Protestant Print I Playne Piers” turns to Tudor appropriation of the Piers Plowman tradition and conducts meticulous detective work. As she observes, other scholars have remarked offhand the presence of rhyme and alliteration in the prose polemic I Playne Piers, as though these features were no more than rhetorical decoration. Cawsey, however, performs a minute formal analysis and hunts down their exemplars or analogues. While concluding that I Playne Piers is “a messy patchwork of various sources” (p. 50), she also suggests that it “may mark a turning point in the printing of plowman texts, since [I Playne Piers’s compilers] . . . recognized the value of the form, not just the content, of medieval sources in arguing the case for the antiquity of Protestantism” (p. 51). In light of this observation, can we but think of Spenser’s poetics in the The Faerie Queene later in the Tudor period?

The Langland of Piers Plowman and a case of mistaken identity is the focus of Thomas A. Prendergast’s “The Work of Robert Langland.” The first to bring the poem to print, Robert Crowley, and then others in suit identified the poem’s author as “Robert” Langland, whom they characterized as one of Wyclif’s first followers, placing the poem not in a late medieval orthodox reformist tradition but in a heterodox line. Later modern critics have contended that Crowley and others invented Piers Plowman’s Lollard origins in order to make a case for Reformation antiquity. Prendergast rejects that conclusion and asserts, “the means by which the group of men discovered him were reflective of the humanistic methods of Erasmus, and involved the creation of a homosocial community that valued the sharing of intellectual work and the recovery of a rapidly disappearing past” (p. 71). Moreover, Prendergast observes that, after the death of Queen Mary and the accession of Queen Elizabeth, “the conditions under which antiquarians operated became more fraught, and something like borrowing a book, even a book with a good reformist pedigree like Piers Plowman, might indicate an unhealthy and dangerous interest in the past” (p. 86), given that England had already once relapsed into Catholicism.

Jesse M Lander’s

“The Monkish Middle Ages: Periodization and Polemic in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments” reminds us that the

English Reformation historian owed more to Augustine, Bede, and Joachim for his

taxonomy of history than he did to early-modern humanists. The Book of Martyrs “displays a particular

sense of the Middle Ages that owes more to apocalyptic exegesis and

anti-Catholic polemic than to humanist claims for the rebirth of the classical”

(p. 95). The apocalyptically inclined Foxe had already inherited theologies of

history, and, when he described the medieval period, he employed the figure of accumulatio, the congeries or heaping up

of fables and superstitious rituals that accumulated during the Middle Ages.

Regardless, Foxe always teased out signs of an underground True Church that

never wholly left the Church of England even while it was under thrall to Rome.

Jesse M Lander’s

“The Monkish Middle Ages: Periodization and Polemic in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments” reminds us that the

English Reformation historian owed more to Augustine, Bede, and Joachim for his

taxonomy of history than he did to early-modern humanists. The Book of Martyrs “displays a particular

sense of the Middle Ages that owes more to apocalyptic exegesis and

anti-Catholic polemic than to humanist claims for the rebirth of the classical”

(p. 95). The apocalyptically inclined Foxe had already inherited theologies of

history, and, when he described the medieval period, he employed the figure of accumulatio, the congeries or heaping up

of fables and superstitious rituals that accumulated during the Middle Ages.

Regardless, Foxe always teased out signs of an underground True Church that

never wholly left the Church of England even while it was under thrall to Rome.Rome -- or at least Roman law -- is the polemical target examined in Rebecca J. Brackmann’s “‘That auntient authoritie’: Old English Laws in the Writings of William Lambarde.” At a time when their national church was struggling for legitimacy, the English also worked to establish the antiquity -- and the superiority -- of their laws and customs over foreign Continental impositions, with jurist William Lambarde as the paragon of this effort. In Lambarde’s analysis, English common law is understood as indigenous, and those who break it become foreigners, with any bad habits appropriated by the English seen as coming from outside. They are infection, and Lambarde developed a complex series of medical metaphors about the body politic, or as Brackmann observes: “law is no longer just the medicine by which the bad humors are purged, but instead has become the very soul of human society” (p. 123).

Bringing up the bodies and the law in the next chapter, “The Rebel Kiss: Jack Cade, Shakespeare, and the Chroniclers,” Kellie Robertson explores not only Shakespeare’s appropriation of the historical record of Cade’s 1450 rebellion (already a “cottage industry” in Shakespeare studies, Robertson allows) but also how the chronicles (Hall and Holinshed) themselves appropriated the historical events, particularly Cade’s supposed agitprop theatre of making the decapitated heads of his enemies kiss each other. She finds that “insofar as the act of historical writing reanimates dead bodies, the posthumous kiss in both chronicles and 2 Henry VI is essentially metahistorical, an emblem of the history tellers’ own larger project of refashioning the body politic” (p. 128). What she reads in Shakespeare’s play, then, has less to do with the playwright’s attitudes toward rebellion than with a larger anxiety about the theatrical representation of the dead.

William Kuskin’s “At Hector’s Tomb: Fifteenth-Century Literary History and Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida” offers a tightly argued, compound thesis: literary history must account for the complex relationships between rhetorical forms and their material production, that doing so discloses a persistent set of problems about authorship and form from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, with attention to this complex relationship revealing “an alternative mode of reading literary history, one that describes not medieval otherness and early modern origins but the structural problems of representation implicit in vernacular literary production” (p. 146). What literary history acknowledges is the recursive power of the book, transcending literary history.

This rich volume concludes with “Owning the Middle Ages: History, Trauma, and English Identity” in which Nancy Bradley Warren examines anxieties about Tudor legitimacy represented in “female bodies and the roles those bodies play in legitimating or delegitimating dynastic lineages” (p. 174), which came to the fore during the reign of Elizabeth I. She argues for an unlikely source -- St. Birgitta and Brigittine spirituality -- to which the queen’s supporters, like John Foxe and Edmund Spenser, turned, particularly after the 1569 northern earls’ rebellion and Pope Paul V’s promulgation of the bull Regnans in Excelsis, declaring the queen to be a heretic and absolving the English of allegiance to her.

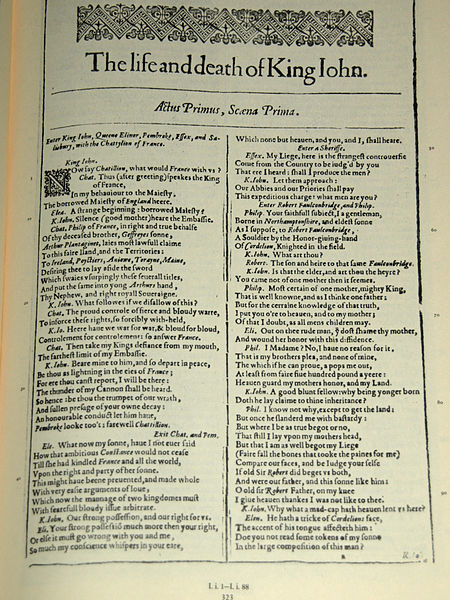

The book includes many useful visuals of medieval manuscripts and early-modern books, as well as a comprehensive bibliography of works cited in the chapters. With its wide scope, it will find readers among students and scholars of literature and history.

In bringing together these chapters into one body of work, Kelen proposes that there is “great scholarly potential that early modern medievalism still holds” since “[f]ar from being a buried past, irrelevant to later periods, the literature, historiography, politics, religion and law of the Middle Ages remained deeply bound up with some very contemporary concerns of the Tudor era” (p. 12). In recent years, this harvest has included such diverse work as David Gaimster and Roberta Gilchrist’s The Archaeology of Reformation 1480 - 1580, Fiona Somerset and Nicholas Watson’s The Vulgar Tongue: Medieval and Postmedieval Vernacularity, Ruth Morse, Helen Cooper and Peter Holland’s Medieval Shakespeare: Pasts and Presents, and Clare Costley King’oo’s Miserere Mei: The Penitential Psalms in Late Medieval and Early Modern England. It seems that we’re all post-medieval now.

Camden,

William. Remains Concerning Britain.

London: John Russell Smith, 1870.

Gaimster,

David, and Roberta Gilchrist, eds. The

Archaeology of Reformation 1480-1580. Leeds, UK: Maney, 2003.

Levy,

F. J. Tudor Historical Thought. San

Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1967.

King’oo,

Clare Costley. Miserere Mei: The

Penitential Psalms in Late Medieval and Early Modern England. Notre Dame,

IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2012.

Morse,

Ruth, Helen Cooper, and Peter Holland, eds. Medieval

Shakespeare: Pasts and Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2013.

Panofsky,

Erwin. “Renaissance and Renascences.” The

Kenyon Review, 6.2 (Spring 1944): 201-236.

Somerset,

Fiona, and Nicholas Watson, ed. The

Vulgar Tongue: Medieval and Postmedieval Vernacularity. University Park, PA: Penn State University

Press, 2003.

Summit,

Jennifer. Memory’s Library: Medieval

Books on Early Modern England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Thomas Lawrence Long

University of Connecticut