Alexis E. Fajardo, Kid Beowulf. 3 vols. Bowler Hat Comics / Kid Beowulf Comics, 2008-2013.

Reviewed by: Jason Tondro (jason.tondro@gmail.com)

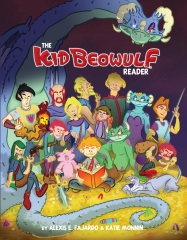

While assembling a list of Beowulf comics for another project, I initially skipped Alexis E. Fajardo's Kid Beowulf series on the grounds that it was not an adaptation of the original poem. While that characterization remains true, it was nevertheless a mistake to dismiss the book. Kid Beowulf is a well-written adventure comic with humor and a strong literary influence that makes it eminently suitable for middle-school readers. More advanced students will find Fajardo's progressive and sympathetic characterization of gender, faith, and culture to be rewarding and provocative. Moreover, a Reader's Guide with study questions, classroom assignments, and other teaching tools is now available, developed by Fajardo and Katie Monnin, a professor of literacy at the University of North Florida, whose outstanding credentials in this regard make her the ideal partner. All of this combines to make the book not only useful in the classroom, but a rarity in the comic marketplace: the sort of comic your daughter, niece or grand-daughter might enjoy.

The Kid Beowulf series is satisfyingly hefty; the three volumes published by Bowler Hat from 2008-2013 add up to 650 pages. In concept, the tale is essentially a prequel; years before their cataclysmic battle in Heorot, Beowulf and his twin brother Grendel are conceived, grow up, and are eventually exiled (Kid Beowulf and the Blood-Bound Oath), whereupon they begin a Heroic Journey through France (Kid Beowulf and the Song of Roland) and Spain (Kid Beowulf and the Rise of El Cid); they meet and adventure with a great many other heroes, including not just Roland and El Cid but Bradamant, Boudicea, and Ogier the Dane. Each book begins with a short 8-12 page adaptation of the source poem, but the rest of each volume is actually a complete re-imagining of the story of Beowulf, Roland and El Cid, virtually from the ground up. In France, for example, we find Ganelon in charge of the kingdom and slowly poisoning Charlemagne with daily doses of arsenic while he maintains Roland's loyalty by flattering his ego through the construction of a magnificent theme park entitled RO-LAND. The Peers are alive but in hiding, and Bradamant has been transplanted from Orlando Furioso to join the French Resistance training in the sewers. The two hundred pages in each volume are not padding or wasted space; there's a lot going on in these books.

Fajardo's influences are not difficult to identify, and he makes no secret of them. I was personally reminded of Matt Wagner's Mage II: The Hero Defined, a story in which King Arthur, Hercules, Prester John and other heroes rub shoulders and misadventures, but the most obvious is probably Asterix the Gaul, who -- along with his partner Obelisk -- even have surrogates in the book as Heathobard ne'er do wells out to murder Beowulf and Grendel to get in Froda's good graces. Literary sources include not only Beowulf, the Matter of France and El Cid, but also other literary works associated with these cultures. For example, Beowulf's mother is named Gertrude, his father appears to him as a ghost, and young Beowulf himself is exiled from the country. Orlando Furioso has already been mentioned, but the footprints of the Three Musketeers in the second volume are everywhere, with Ganelon as Cardinal Richelieu, Turpin playing the role of Athos, and Ogier the Dane as the love-lost Aramis. The fact that Ogier's paramour is a gypsy might be just a curious fact were in not for the presence in the story of a hunchback and repeated use of Notre Dame cathedral. The revolution against Ganelon is both a French Revolution and a French Resistance. A subplot in which Grendel (in a clown suit) and Beowulf (in a dress, playing the girl's part) are forced to perform on stage for money even provides an opening for a discussion of Renaissance theatrical practices. After all this, I was actually a little disappointed when I got to the El Cid chapter and Don Quixote did not appear.

Fajardo's influences are not difficult to identify, and he makes no secret of them. I was personally reminded of Matt Wagner's Mage II: The Hero Defined, a story in which King Arthur, Hercules, Prester John and other heroes rub shoulders and misadventures, but the most obvious is probably Asterix the Gaul, who -- along with his partner Obelisk -- even have surrogates in the book as Heathobard ne'er do wells out to murder Beowulf and Grendel to get in Froda's good graces. Literary sources include not only Beowulf, the Matter of France and El Cid, but also other literary works associated with these cultures. For example, Beowulf's mother is named Gertrude, his father appears to him as a ghost, and young Beowulf himself is exiled from the country. Orlando Furioso has already been mentioned, but the footprints of the Three Musketeers in the second volume are everywhere, with Ganelon as Cardinal Richelieu, Turpin playing the role of Athos, and Ogier the Dane as the love-lost Aramis. The fact that Ogier's paramour is a gypsy might be just a curious fact were in not for the presence in the story of a hunchback and repeated use of Notre Dame cathedral. The revolution against Ganelon is both a French Revolution and a French Resistance. A subplot in which Grendel (in a clown suit) and Beowulf (in a dress, playing the girl's part) are forced to perform on stage for money even provides an opening for a discussion of Renaissance theatrical practices. After all this, I was actually a little disappointed when I got to the El Cid chapter and Don Quixote did not appear.

After all of this, it can be difficult to write about the art on Kid Beowulf. Fajardo is entirely self-taught; he began with comic strips for his college paper and Kid Beowulf went through two previous versions before being entirely re-written and drawn for the editions from Bowler Hat. The most common adjective used to describe the style of Kid Beowulf is "cartoony," which is true as far as it goes, but which doesn't really say much. Fajardo's character designs are very strong and his technical skill improves throughout the series. The art excels at physical comedy and Fajardo has a great sense of timing. Many pages, however, seem rushed. When characters engage in conversation, or when an action scene arrives, backgrounds often entirely disappear and we are left with characters speaking, fighting, or leaping through a rootless empty space. Sometimes there is an effort to mask this with shades of grayscale, but because this shading is so obviously artificial, it does nothing to truly alleviate the problem and, in fact, contrasts painfully with Fajardo’s line work, making the situation even worse. Composing, drawing, and revising 650 pages is a monumental task which I can only appreciate, but Kid Beowulf and his brother Grendel would be better served if they moved through a world which was more reliably drawn and more carefully shaded.

Fajardo can do this; his work is full of panels and pages which are beautiful and dramatic. He cites Jeff Smith's Bone as one of his influences, and he could not ask for a better teacher. While I am sure there are panels and pages where Smith has scrimped in his portrayal of scene or background, such panels are hard to find. Even when Smith creates a background without line work, his use of color nevertheless creates trees, snow and sky. Look, too, to Herge's legendary background work in Tintin. McCloud's analysis of "cartoony" art styles and their relationship to realism is worth remembering here; like Bone and Tintin, Kid Beowulf is a book whose protagonists are made with open lines, curves, and a lack of realistic detail, empowering readers to project themselves in and don the character as a mask. This is very effective, but it is only half the equation. The physical detail of the world around those characters, in contrast, is not "cartoony," but physically real and sensually stimulating. McCloud calls this "one set of lines to see, another set of lines to be,"1 and, when Fajardo does it, such as in Ogier's trek from Spain back to Geatland, it works. He just needs to do it more often.

Reviewed by: Jason Tondro (jason.tondro@gmail.com)

While assembling a list of Beowulf comics for another project, I initially skipped Alexis E. Fajardo's Kid Beowulf series on the grounds that it was not an adaptation of the original poem. While that characterization remains true, it was nevertheless a mistake to dismiss the book. Kid Beowulf is a well-written adventure comic with humor and a strong literary influence that makes it eminently suitable for middle-school readers. More advanced students will find Fajardo's progressive and sympathetic characterization of gender, faith, and culture to be rewarding and provocative. Moreover, a Reader's Guide with study questions, classroom assignments, and other teaching tools is now available, developed by Fajardo and Katie Monnin, a professor of literacy at the University of North Florida, whose outstanding credentials in this regard make her the ideal partner. All of this combines to make the book not only useful in the classroom, but a rarity in the comic marketplace: the sort of comic your daughter, niece or grand-daughter might enjoy.

The Kid Beowulf series is satisfyingly hefty; the three volumes published by Bowler Hat from 2008-2013 add up to 650 pages. In concept, the tale is essentially a prequel; years before their cataclysmic battle in Heorot, Beowulf and his twin brother Grendel are conceived, grow up, and are eventually exiled (Kid Beowulf and the Blood-Bound Oath), whereupon they begin a Heroic Journey through France (Kid Beowulf and the Song of Roland) and Spain (Kid Beowulf and the Rise of El Cid); they meet and adventure with a great many other heroes, including not just Roland and El Cid but Bradamant, Boudicea, and Ogier the Dane. Each book begins with a short 8-12 page adaptation of the source poem, but the rest of each volume is actually a complete re-imagining of the story of Beowulf, Roland and El Cid, virtually from the ground up. In France, for example, we find Ganelon in charge of the kingdom and slowly poisoning Charlemagne with daily doses of arsenic while he maintains Roland's loyalty by flattering his ego through the construction of a magnificent theme park entitled RO-LAND. The Peers are alive but in hiding, and Bradamant has been transplanted from Orlando Furioso to join the French Resistance training in the sewers. The two hundred pages in each volume are not padding or wasted space; there's a lot going on in these books.

After all of this, it can be difficult to write about the art on Kid Beowulf. Fajardo is entirely self-taught; he began with comic strips for his college paper and Kid Beowulf went through two previous versions before being entirely re-written and drawn for the editions from Bowler Hat. The most common adjective used to describe the style of Kid Beowulf is "cartoony," which is true as far as it goes, but which doesn't really say much. Fajardo's character designs are very strong and his technical skill improves throughout the series. The art excels at physical comedy and Fajardo has a great sense of timing. Many pages, however, seem rushed. When characters engage in conversation, or when an action scene arrives, backgrounds often entirely disappear and we are left with characters speaking, fighting, or leaping through a rootless empty space. Sometimes there is an effort to mask this with shades of grayscale, but because this shading is so obviously artificial, it does nothing to truly alleviate the problem and, in fact, contrasts painfully with Fajardo’s line work, making the situation even worse. Composing, drawing, and revising 650 pages is a monumental task which I can only appreciate, but Kid Beowulf and his brother Grendel would be better served if they moved through a world which was more reliably drawn and more carefully shaded.

Fajardo can do this; his work is full of panels and pages which are beautiful and dramatic. He cites Jeff Smith's Bone as one of his influences, and he could not ask for a better teacher. While I am sure there are panels and pages where Smith has scrimped in his portrayal of scene or background, such panels are hard to find. Even when Smith creates a background without line work, his use of color nevertheless creates trees, snow and sky. Look, too, to Herge's legendary background work in Tintin. McCloud's analysis of "cartoony" art styles and their relationship to realism is worth remembering here; like Bone and Tintin, Kid Beowulf is a book whose protagonists are made with open lines, curves, and a lack of realistic detail, empowering readers to project themselves in and don the character as a mask. This is very effective, but it is only half the equation. The physical detail of the world around those characters, in contrast, is not "cartoony," but physically real and sensually stimulating. McCloud calls this "one set of lines to see, another set of lines to be,"1 and, when Fajardo does it, such as in Ogier's trek from Spain back to Geatland, it works. He just needs to do it more often.

|

| Selection from Kid Beowulf and the Rise of El Cid |

The same attention to characterization is present when Beowulf and Grendel travel among French and Spaniards, meeting Muslims, Jews, and even followers of Mithras, all of whom are presented fairly and with sympathy. The Song of Roland is an especially problematic text when it comes to the depiction of faith; having once attempted to write a film adaptation of it, I find it almost impossible to discuss without apologizing. But as Fajardo works through both the second and third volumes, his precedent for throwing out whatever does not suit his purpose, and mixing in whatever does, allows him to present a tale in which the characters are sympathetic human beings, not monstered others. The Muslim characters in this book refer to God frequently, but always as God, not Allah; this alone is going to be enough to prompt class discussion, especially if your classes happen to be located, as mine are, in the rural South. Some Christians seek war, while some Muslims seek peace, and the opposite is also true. No one culture or faith is entirely sympathetic or entirely alien. It would have been easy, in a comics marketplace home to Frank Miller's Holy Terror, in a country awash in post-9/11 "culture war" language, to portray the Muslims of Grenada, Cordoba and Toledo as wicked barbarians. That this is not done is Kid Beowulf's greatest strength, and the portrayal of culture, gender, and faith makes Kid Beowulf a useful read even for advanced students.

Finally, it worth taking a little time to talk about the future of Kid Beowulf. The draft of the Reader’s Guide that I had a chance to see provided valuable and entertaining insight into the origin of the book, its characters, and Fajardo's creative process. It is intended to be used with the Common Core and is marked for grades 6-12. It's not fair to judge a draft, and so I will not attempt it; I will note that the Guide includes lists of literary sources which went into each volume. While these sources include, for example, Heaney's translation of Beowulf and Gareth Hinds' masterful adaptation into the comics form, I would like to see the addition of other literature which is less directly referenced. For example, since the use of Hamlet is undeniable in the book, why can't we include that play, along with Three Musketeers and Hunchback of Notre Dame in the resources for Kid Beowulf and the Song of Roland? If one of Kid Beowulf's charms is that it functions as "gateway literature," then surely we should open that gate as wide as possible? As part of this move into middle school and high school classrooms, Kid Beowulf is also transitioning to an online webcomic, and Fajardo is taking this opportunity to add color to all 650 pages. This effort, which no doubt requires enormous work, is to be applauded. Other comics creators, like Eric Shanower, creator of the amazing Age of Bronze, have demonstrated just how laborious and slow this process can be, even when the rewards are great. It is my hope that Fajardo is able to follow through on this move to an online color webcomic, and perhaps take the opportunity to address some of the background and shading challenges which occasionally plague the book.

In the meantime, the print editions of Kid Beowulf remain a fun, engaging, and thought-provoking experience which rewards the close read.

*On November 5, 2013, the Kid Beowulf series was relaunched as a full-color webcomic. It will update twice a week beginning with book one. Previews are running on Tapastic, the site which will feature the webcomic, and can be viewed here: http://tapastic.com/series/Blood-Bound-Oath

Jason Tondro

College of Coastal Georgia

[ 1 ] See the second chapter of Understanding Comics for this discussion; McCloud’s use of Tintin as an example of “one set of lines to see, another set of lines to be” is on page 43.

[ 1 ] See the second chapter of Understanding Comics for this discussion; McCloud’s use of Tintin as an example of “one set of lines to see, another set of lines to be” is on page 43.